1 selective logging

Early white settlers used selective logging to control the Otway rainforest with the axe and the match.

They selected and expertly chopped down the tallest giant trees. Teams of cattle slowly dragged each huge log from the steep forest through mud and rain. One of the selective logging workers joked that the beech trees were so big in the Otways that cattle could back up their trunks and turn around.

Logs from selective logging went to Melbourne by boat, long before the Great Ocean Road was made.

Selective logging left most of the forest intact, but it had some effect on the Otways.

2 clearfelling

In the 1970s and 1980s clearfelling made whole patches of Otway forest disappear. Log trucks, chainsaws and bulldozers had arrived. Each patch of clearfelling was called a “coupe”, a French word meaning a blow. Coupes were restricted in size, and only a few coupes were allowed in each valley during a logging season. Clearfelling the Otway forests has not stopped the same forest from producing drinking water for Victoria.

Clearfelling starts in summer so trucks can get in and out and creeks can recover. Industrial clearfelling effects native forest and upsets the balance of creatures and plants forever. You can’t really predict rainfall, but in the Otways rain can move mountains and clearfelling has caused significant pollution and soil erosion.

The value of a log could be weighed against its potential damage to the environment, but the royalties paid scarcely meet the environmental cost.

The old log companies persist today, supported by generous grants and awards. Log tracks go through the forest to nowhere and may lead tourists astray. Such is the power of the log.

Gradually the chase for the tallest and straightest logs morphed into a woodchip industry –any log that would sit on the sawbench would do for the chipper. Mountains of woodchips waited in the port of Geelong to make paper in Japan.

The wet forest logs had to be regenerated by fire and even bombed with napalm to get them to burn. The Otways could no longer support the demands of a greedy industry. Slowly the forest had changed forever.

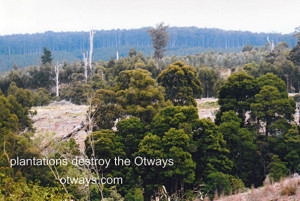

3 plantations

At first they were rows of non-native pine trees. Then we saw acres of bluegum plantations. The log industry and its plantations now scar the Otways forever.

Steep slopes and high rainfall do not stop plantations. Ignorance about farming trees like a crop of turnips is added to the habit of ripping them out at six years of age with horrible chainsaw chopping and stripping machines. Then they douse the young trees with poison chemicals. Take a look at the stacks of timber near Colac in the Otways.

4 tourism

The Otways is the greatest tourism attraction in the region but it’s pretty much ignored. You would think a waterfall was something to treasure.

Apollo Bay has a thriving tourism industry even though it is only marketed as a brief bus stop on the way to the 12 apostles. A short drive along the Paradise road reveals lovely farms and forested valleys but no longer leads visitors to the secret Marriners’ Falls. These waterfalls have been purposefully closed off by the Victorian government even though the federal government has provided one of the best bridges in the region, the bridge to nowhere.

It would be only a short walk from the new bridge to these falls. They were featured on all the old postcards. I used to take my kids and visitors there, but the nasty fence closes off the path along the riverside to the falls and the precious experience has been lost.

One wonders what happened to cause a person to be injured by a falling tree and whether these falls could be secured again for tourism.

But it is still Paradise, a paradise of beech trees, tree ferns and hanging vines, threatened species like sugar gliders and at night the glow worms along the valley road.

5 stop logging

In the newly created Otway National Park I was arrested for trying to stop logging in the Otways –even if it was only for a few hours.

In the 1980s log coupes were hidden from the public gaze. I had started the “Save the Otways” protest group allied to the Otway Environment Group, and this website with the help of a friend at Deakin University.

A small group of visitors and curious locals toured the Otways by bus to discover some of the hidden log coupes with me. We were helped by Noddie (Paul Hill) who wrote about the Otways and later became a hermit in the Otway National Park for about 15 years.

A stringer and a journalist from ABC television had covered some of our efforts in the Otways to stop logging, but this was to be the most amazing day of all. Some 30 local people gathered as witnesses before the Geelong media arrived.

The logging company continued hauling a log up a steep slope towards us. They refused to stop logging. The bulldozer driver actually tapped my ankles with the blade as we struggled up the slope in the mud towards the clearing where the log was to be loaded with all the other logs they had gathered. Chainsaw operators and trucks were around.

As the log slid through the forest on a rope, a piece of wood flew up and embedded itself in one brave man’s leg. He said nothing. I threatened to grab the key of the dozer and throw it into the forest.

Finally the forestry officer screamed stop logging and it was over.

After three hours a female police officer from Warrnambool arrested me, a bedraggled figure covered in oil and grease in the back of a logger’s ute. The media finally arrived and took a posed photo of me standing in front of a log truck.

It was a nasty drive through twisting roads to the new lockup in Colac. I was kept there for about 40 hours. There is nothing like the big door closing on you and you’re on your own.

To this day I am grateful to the person who wrote yoga exercises in biro on the lining of the thin mattress on top of the concrete block that served as my bed.

6 beech tree

The Otways beech tree is rarely mentioned in government banter about logs. The Nothofagus Cunninghamii likes wet gullies and does not regenerate after fire. Its leaves are dark green, a bit like the maiden hair fern. It’s closely related to Tasmania’s beech tree, and like our white goshawk it seems to have a cousin over the water. With the glow worms and carnivorous black snails, kookaburras and gliders the beech trees at Marriners’ Falls live in other wet pockets of the Otways.

Otway rainforests are precious but we have to look after them ourselves. Gum trees straight enough to go through the saw mills are fair game but the beech tree is ours. With its strange ancient leaves, uniquely beautiful red timber and buttresses maybe the beech tree is not attractive to industry. But it’s vulnerable to the poison, the trucks, the dozers and back burning.

So here ends the story of a log – a living beech tree with its own secrets, something worth saving and dependent on you for its survival.